Last Updated: January 14, 2026

TL;DR

- A quitclaim deed transfers any ownership interest the grantor has, without guarantees about title or ownership.

- It's best suited for transfers between trusted parties, like family members or into a trust.

- Common mistakes include ignoring title issues, unpaid liens, or unclear property descriptions.

- Proper execution requires full legal names, notarization, and timely recording with the county.

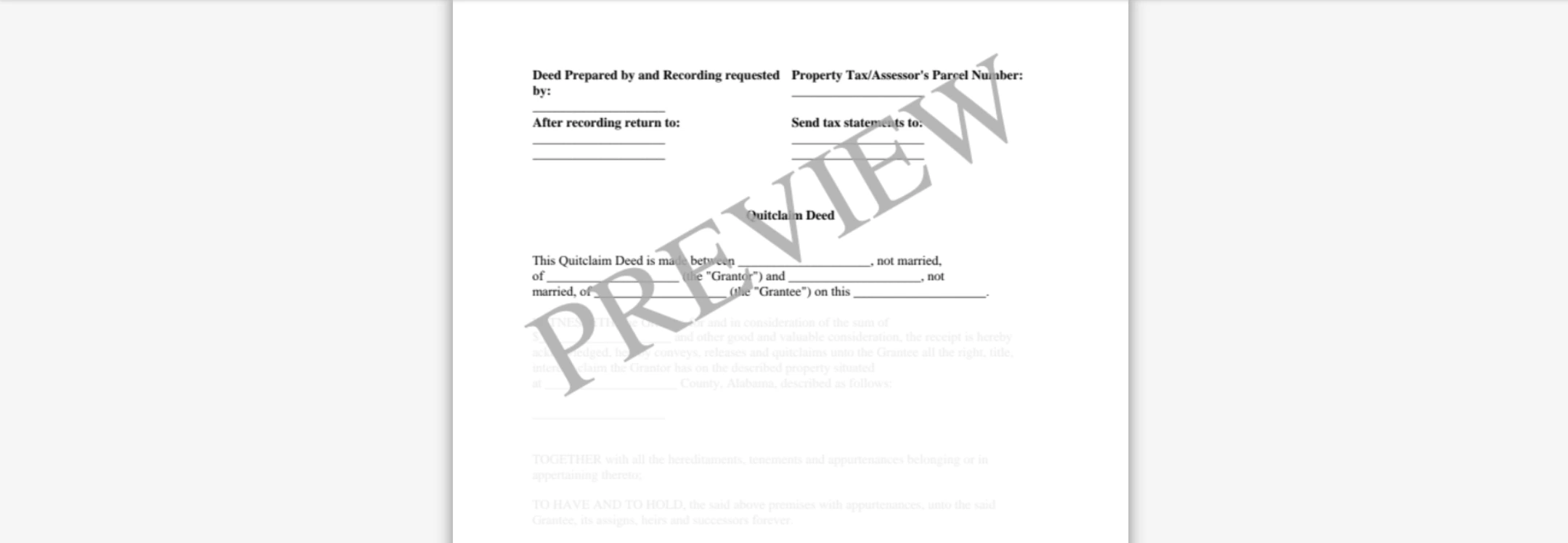

- To put it all into practice, the blog shows how to create a quitclaim deed using Ziji Legal Forms’ customizable templates.

Key Terms Explained

To start, let’s clarify a few fundamental terms that will help you understand quitclaim deeds better:

Deed

A legal document that transfers ownership of real property from one party (the grantor) to another (the grantee). The deed is what actually conveys title (ownership) to the property when properly executed and delivered. Different types of deeds provide different levels of assurance about the property’s title.

Title

In real estate, “title” refers to the legal ownership rights to a property. It’s not a physical document, but rather the concept of ownership. Having clear title means you own the property free of any undisclosed liens or claims. (Think of the deed as the paper that transfers the title rights.)

Grantor

The person or party who is transferring their interest in the property. In a deed, the grantor is the one “giving up” or conveying ownership rights.

Grantee

The person or party who is receiving the interest in the property. The grantee is the new owner who takes title through the deed.

Quitclaim Deed

A type of deed in which the grantor “quits” any claim they have to the property, transferring their interest to the grantee without any warranties. The grantor makes no promises about the title’s quality or even whether they truly own the property. A quitclaim deed simply conveys whatever ownership interest the grantor currently has, if any, to the grantee. (Because of this, it’s sometimes called a “non-warranty deed.”) All quitclaim deed does is release the grantor’s interest; it does not guarantee a clear title.

Warranty Deed

A deed that includes guarantees about the title. In a general warranty deed, the grantor assures the grantee that the title is clear of any liens or claims and promises to defend that title against any future challenges. This offers the highest level of protection to the grantee. A special warranty deed gives a more limited guarantee, typically that no issues arose during the current owner’s period of ownership. Both types of warranty deeds contrast with a quitclaim deed, which provides no such assurances.

Legal Description

The precise, legally recognized description of the property being transferred. This is more detailed than a street address, it could be a lot number, metes and bounds description, or other survey description that uniquely identifies the property in official records. The legal description is required in the deed to ensure the property is correctly identified.

Recording

The act of filing a document, such as a deed, with the appropriate government office. This is usually done at the County Recorder or Register of Deeds. Recording a deed in the county where the property is located puts the world on notice of the change in ownership. It’s a crucial step that makes the transfer official and part of the public record.

Clear Title

A title free of liens, encumbrances, or other ownership claims. Clear title means no one else can legally claim an interest in the property. If there is a “cloud on title,” it means there is some claim or unresolved issue (for example, an heir who didn’t sign off, or a disputed old lien) that casts doubt on the owner’s full rights. One way to clear a cloud on title is often to have the person with a potential claim sign a quitclaim deed to relinquish their interest.

Now that we have these basic terms defined, let’s explore the biggest mistakes to watch out for when using a quitclaim deed. Avoiding these common errors will help ensure your property transfer is legally effective and free of unwelcome surprises.

Mistake 1: Not Understanding What a Quitclaim Deed Really Does

One of the most fundamental mistakes is misunderstanding the nature of a quitclaim deed. People frequently mispronounce or misspell it as a “quick claim deed,” thinking it’s just a speedy way to transfer property. (In fact, many people search for “what is a quit claim deed” or “quick claim deed form” when they’re in a hurry to change ownership.) It’s true that quitclaim deeds are relatively quick and easy to execute, but the name is actually “quitclaim”, as in “quitting” your claim on a property. The crucial thing to understand is what isn’t happening with a quitclaim deed: the deed does not guarantee you actually own the property or that the title is clear.

Unlike a warranty deed, which assures the grantee that the title is good, marketable, and free of liens or other claims, a quitclaim deed makes no promises at all about the status of the title. The grantor is simply saying, “I give you whatever interest I have in this property – which might be nothing.” If the grantor has no legitimate ownership interest, then the grantee gets no ownership despite the deed. For example, if John Doe uses a quitclaim deed to transfer the Empire State Building to you, that deed transfers only John’s interest in the building – which, unless John actually owns it, is zero. You can see how a quitclaim deed could be abused or lead to false confidence if you don’t fully grasp this.

How to avoid this mistake

Make sure you understand the limits of a quitclaim deed. It’s essentially a relinquishment of whatever rights the grantor may have. If you’re the grantee, be aware that you’re not receiving any guarantee of ownership or clear title. If you’re the grantor, know that once you sign and deliver a quitclaim deed, you give up all the interest you had, if any, to the grantee. In short, don’t assume a quitclaim deed is a magic “quick fix” for property transfers. It’s a specific tool with a narrow purpose. If you need more certainty or protection (for instance, you want assurance that you truly own what’s being transferred), a quitclaim deed is not the right instrument. Consider using a different type of deed or arrangement in those cases, or consult a professional. The rest of this list will further illuminate these issues.

Mistake 2: Using a Quitclaim Deed in the Wrong Situations

Quitclaim deeds have very specific appropriate uses and using them in the wrong context is a common mistake. By design, quitclaim deeds are best suited for low-risk transfers between people who know and trust each other, or for correcting minor title issues. For example, adding a spouse to a title after marriage, transferring property within family, putting property into a trust or LLC you own, or fixing a typo on an earlier deed are all typical uses for quitclaim deeds. In these scenarios, the parties aren’t strangers and no money, or very little money, is changing hands, so the lack of warranty isn’t as big a concern.

However, you should not use a quitclaim deed for normal real estate sales or other high-stakes transactions. If you’re buying a home from someone you don’t know well and you hand them money in exchange for a quitclaim deed, you are taking a huge risk. Since a quitclaim doesn’t guarantee clear ownership, you could pay for a property and later discover the seller (grantor) didn’t have good title or that there are liens on the property. You’d have no legal recourse or warranty to protect you in that case. That’s why, in a typical home sale, a warranty deed, often accompanied by title insurance, is used instead – it guarantees the seller has the right to transfer the property and that it’s free of hidden encumbrances. By contrast, using a quitclaim in a sale to an unrelated party should raise red flags. In fact, real estate professionals often say never use a quitclaim deed with a stranger, and even be cautious using one with family unless you’re 100% sure of the situation.

Similarly, do not use a quitclaim deed for large, complex property deals or where loans and title insurance are involved. Lenders and title companies usually won’t accept quitclaim deeds in place of more formal transfers, because they provide no guarantees. If you’re taking out a mortgage or refinancing, a quitclaim deed isn’t appropriate to transfer ownership into someone else’s name at closing. The bank will want the assurance of a warranty deed or similar.

How to avoid this mistake

Use quitclaim deeds only in the limited scenarios where they make sense. If you’re unsure, ask yourself: Is this an informal transfer or a gift between known parties? Am I simply fixing a clerical error? Those are the kinds of situations for quitclaim deeds. If instead you’re effectively “selling” the property or transferring to someone who would want assurance of clear title, opt for a warranty deed or other proper instrument. When in doubt, consult a real estate attorney. (For more guidance on when a quitclaim deed is appropriate, see our complete guide on using quitclaim deeds, as well as our article on warranty deeds for comparison.) Using the right tool for the job is half the battle in avoiding quitclaim deed problems.

Mistake 3: Not Verifying Ownership and Title Status (Assuming “It’s All Good”)

Another major mistake is failing to verify the status of the property’s title before transferring or accepting a quitclaim deed. Because a quitclaim deed offers zero protection, it’s critical that the parties understand exactly what interest is being transferred. If you’re the grantee, you should confirm that the grantor actually has an ownership interest to convey and find out if anyone else has claims to the property. Simply put, don’t skip the due diligence because a quitclaim deed itself won’t guarantee anything for you.

We’ve already noted that with a quitclaim deed, if the grantor doesn’t truly own the property, the grantee gets nothing. This scenario can and does happen. For instance, imagine an elderly parent intends to deed the family home to one adult child via quitclaim. If it turns out the parent doesn’t actually hold clear title (maybe the house was never probated properly after a grandparent’s death, or there’s a forgotten co-owner) then that quitclaim deed might be ineffective. The child may not actually own the property at all, even though they have a signed deed in hand. Such issues often surface later when the grantee tries to sell the property and a title search reveals “clouds” (problems) on title. It can be a nasty surprise to discover that a quitclaim transfer didn’t give you true ownership.

Likewise, even if the grantor does have title, there might be outstanding liens, taxes, or claims on the property. A quitclaim deed won’t wipe those away (more on that in the next mistake). So if you accept a quitclaim deed without checking for things like liens or judgments, you could be stepping into a mess. Title searches and, ideally, title insurance exist to uncover and handle these issues in a standard sale – but people often skip those in a casual quitclaim transfer. Skipping them is a mistake unless you are absolutely sure of the property’s history.

How to avoid this mistake

If you’re receiving property via quitclaim, do your homework on the title beforehand. This can be as simple as searching the county records for past deeds or liens, or as thorough as hiring a title company or attorney to do a title search. You want to confirm that the grantor has the ownership interest they think they have, and identify any encumbrances, like liens or other owners. Remember, a quitclaim deed comes with “no guarantees or warranties regarding the property’s title”, so it’s on you as the grantee to ensure the title is acceptable. If anything looks off (for example, the grantor’s name isn’t exactly the same on the prior deed, or a third party has a recorded interest), address it before transferring by quitclaim. It might mean using a different type of deed or having others sign off as well.

If you’re the grantor, double-check that you’re describing exactly what interest you intend to transfer (no more, no less). Verify that you indeed have the rights you think you do. It can be wise to provide or obtain a recent title report even in a family transaction, just so everyone’s on the same page. In summary, never assume everything is fine with the title simply because you trust the other person. Verify the key details; who owns what, and what condition the title is in because the quitclaim deed itself won’t do it for you.

Mistake 4: Overlooking Liens, Mortgages, and Other Existing Debt

A very common misconception is that a quitclaim deed somehow removes financial obligations like mortgages or liens from the property. This is absolutely not the case. A quitclaim deed only transfers whatever ownership the grantor has; it does not affect mortgages, taxes, or other liens that are tied to the property. People who don’t realize this can make serious mistakes. Let’s break down two perspectives:

From the Grantor’s perspective

Say you quitclaim a property to someone else (for example, transferring your house to your ex-spouse during a divorce). If that property has a mortgage on it that you originally took out, you are still on the hook for that mortgage even after you’re no longer the owner, unless the loan is formally satisfied or refinanced. The quitclaim deed does nothing to remove your name from the promissory note or mortgage contract. This can be a nasty surprise: you might think “I signed over the house, it’s not mine anymore,” but the bank doesn’t care. They care about who promised to pay the loan. If the person who got the house (your ex, in this example) doesn’t make the mortgage payments, your credit can be damaged and the bank can still come after you for the debt. In order to truly get your name off a mortgage, the other party typically must refinance the loan in their own name or pay it off. Simply quitclaiming the deed does not accomplish that.

From the Grantee’s perspective

If you receive a property via quitclaim that has debts or liens attached like a mortgage, tax lien, or judgment lien, those encumbrances remain attached to the property. The person who gave you the quitclaim deed might remain personally liable for, say, the mortgage – but the lender still has a lien on the property itself, and they can foreclose on the property if the loan isn’t paid. That means as the new owner, you could lose the property if the debt isn’t satisfied, even though you never signed for the loan. Similarly, if there’s a tax lien or contractor’s lien, that lien stays with the property; you either have to live with it or clear it by paying it off to have full title. A quitclaim deed doesn’t give any assurances that the property is free and clear of such claims.

Another scenario: transferring property to try to avoid creditors or legal judgments. Some people think they can “quitclaim” their property to a friend or relative to avoid it being taken in a lawsuit or to dodge a creditor. Not only is that legally dubious and potentially fraudulent, it often doesn’t work – liens and judgments may still attach or be enforceable, especially if the transfer was made to evade debts.

How to avoid this mistake

Always account for mortgages and liens before using a quitclaim deed. If you’re parting with the property (grantor) and there’s a mortgage, arrange for that loan to be paid off or refinanced by the grantee before or at the time of transfer if at all possible. At minimum, understand that you’ll remain liable to the bank. Put any agreement with the grantee in writing about who will pay the mortgage going forward, but know that doesn’t bind the lender. If you’re the one receiving the property, do a thorough check for liens, unpaid taxes, or other debts on the property. You can usually search the county recorder’s records for liens, or get a title company to do it. If a lien exists, consider whether it’s worth accepting the quitclaim. You may insist the grantor clear it first. Never assume a quitclaim deed wipes out liens – it doesn’t. As one legal source puts it, taking your name off a deed (via quitclaim) “doesn’t eliminate your obligation toward any debts associated with the property”, and conversely, receiving a quitclaim deed doesn’t eliminate existing liens on that property. The debts stay unless properly addressed through other means.

Finally, be mindful of due-on-sale clauses in mortgages. Many mortgages have a clause that if the property is transferred to someone else, the lender can demand immediate payment of the balance (they might call the loan due). While in practice lenders may not always enforce this, it’s a risk. Certain transfers (to a spouse, or into a living trust for estate planning) are exempt from due-on-sale under federal law, but others are not. If you quitclaim a mortgaged property without the bank’s consent, you’re potentially triggering the loan’s due-on-sale clause. It’s another reason to proceed with caution and communicate with the lender if needed before transferring the deed.

Mistake 5: Providing an Incomplete or Incorrect Property Description

One of the most technical, yet crucial, part of any deed is the property description. This isn’t just the street address of the property, but the formal legal description (for example, lot and block numbers, metes and bounds, parcel ID, etc., as found on a prior deed or title document). A common mistake is failing to include a full, accurate legal description of the property in the quitclaim deed. If the property isn’t described clearly enough, the deed could be deemed invalid or at least ineffective in transferring the intended parcel.

For instance, writing “123 Maple Street, Springfield” might not be sufficient if the legal description in the county records is “Lot 5, Block 3 of Oakwood Subdivision, as recorded in Map Book 20, Page 5, Springfield County.” Typos, incorrect lot numbers, or missing parts of the description can lead to an “ambiguous description” that doesn’t conclusively point to the property you meant to transfer. In a worst-case scenario, an error like this can create a “cloud on title” – a situation where it’s unclear who owns what, because the deed’s description doesn’t match any known parcel perfectly, or overlaps with another. This could require legal action or a corrective deed to fix later.

Including no legal description at all (or just a very cursory one) is a serious mistake. Most states require that a deed identify the property being conveyed with particularity. In fact, a quitclaim deed “requires a legal description of the property being deeded, the county in which the property is located,” etc., to be valid. Simply putting a tax ID or an address alone might not meet this requirement. Even minor mistakes like a one-digit error in a lot number, or omitting the unit number for a condo, can nullify the intended effect.

How to avoid this mistake

When preparing the quitclaim deed, always use the full legal description of the property exactly as it appears on the last deed or official records. You can find this description on your own deed (if you have the title to the property now) or in the public land records. Don’t paraphrase. It’s safest to copy and paste (or re-type verbatim) the legal description. Many counties allow you to attach the full legal description as an exhibit if it’s long. Double-check all numbers (lot numbers, section, township, range, etc.) and spellings. If the property is a condominium or part of a larger tract, make sure every relevant detail is included.

If you’re unsure how to get the legal description, visit the county recorder’s or assessor’s website; often you can search by address or parcel number and find the recorded description. Some quitclaim deed forms have a blank for the legal description – use it diligently. Never leave it blank or “TBD.” An unambiguous, specific description is what legally “pins” the deed to the actual piece of real estate intended. Remember, a deed must clearly state what property is being transferred.

Finally, after drafting the deed, read the description back and imagine: would a stranger be able to go to the county records and identify exactly which parcel this refers to? If yes, you’re in good shape. If not, or if you’re at all confused by it, fix it before signing. Taking the time to get the property description right is key; it’s much simpler to do it correctly now than to clean up a mistaken deed later.

Mistake 6: Errors in the Parties’ Names or Missing Information about the Parties

Similar to describing the property correctly, it’s vital to correctly identify the parties (grantor and grantee) on the quitclaim deed. Mistakes like misspelling a name, using a nickname instead of the legal name, or omitting a name altogether can create issues. The deed should typically use the full legal names of the grantor(s) and grantee(s) as they appear on IDs or existing title documents.

If there are multiple grantors or grantees, a common mistake is not including all of them or not being clear about their interests. For instance, suppose a married couple jointly owns a house. Generally, both spouses should sign as grantors on a quitclaim deed transferring that house, even if only one spouse’s name was originally on the title (depending on state laws regarding marital property). If only one signs, the other’s interest, if any, isn’t transferred, leading to an incomplete conveyance. Similarly, if the quitclaim deed is granting to more than one grantee (say, to two siblings), you should name both siblings clearly as grantees. Moreover, you might need to specify how they will hold title together (e.g., joint tenants with right of survivorship, or tenants in common).

Another piece of information often overlooked is the address of the parties. Many jurisdictions require that the deed list the mailing address of the grantee (for tax and record-keeping purposes). Some also want the grantor’s address. It’s usually a simple detail, but forgetting to include required party addresses on the deed can cause the recorder to reject it or at least complicate matters.

And let’s not forget consideration which is the amount, if any, being paid for the transfer. Quitclaim deeds often transfer property “for love and affection” or for a token amount like $1. While many quitclaims among family have no real purchase price, some states still want you to state some consideration even if it’s nominal or check a box that it’s a gift. Leaving the consideration section blank or writing something noncommittal like “N/A” might be a mistake. It’s usually better to put “$10 and other valuable consideration” (a common placeholder) or whatever nominal amount your state uses, or explicitly indicate it’s a gift transfer if applicable. An “insufficient consideration” is an issue in some jurisdiction to validate the deed so pay attention to that part of the form as well.

How to avoid this mistake

Double-check all names and party details on the quitclaim deed. Use full legal names and make sure they’re spelled correctly throughout – check against driver’s licenses or passports if necessary. Small details like middle initials can matter. It’s better to include a middle initial or name if it was on the prior deed.

Ensure that every current owner who needs to sign is actually signing. If John Doe and Jane Doe own a house together, and they want to quitclaim it to their son, both John and Jane should be listed as grantors and should sign the deed. If you’re not sure who exactly is on the current title, look at the latest deed or title report to see.

When listing grantees, put all their names and consider adding wording on how they take title together. If unsure, you might leave the default, but know that leaving it blank means the law will assume a certain co-tenancy.

Include the addresses as required. Typically, after the legal description, many deed forms have a line for “Mail future tax statements to: [Grantee’s Name and Address].” Fill that in so there’s a record of where the property tax bill and other communications should go after the transfer.

Finally, fill in the consideration line properly. If it’s truly a gift or family transfer, you might put “$10.00” or check a box for gift transfer if the form has it. If there’s an actual sale price, put that. The key is not to leave the field empty or ambiguous.

Before finalizing, read the deed and ask: Can someone reading this identify who is giving up rights, who is receiving them, and what property is involved, without confusion? If yes, you’ve done it right. If no, correct the names/descriptions accordingly. Getting the names and details right ensures the quitclaim deed will hold up and won’t require correction later.

Mistake 7: Not Signing and Notarizing the Deed Properly

Signing a deed might sound straightforward, but you’d be surprised how many quitclaim deeds are rendered useless or rejected because of execution errors. Two common mistakes in this area are: not signing the deed correctly and not getting the deed properly notarized (and witnessed, if required).

First, who needs to sign? Generally, the grantor (person transferring the property) must sign the quitclaim deed. The grantee usually does not need to sign for a quitclaim to be valid (because the grantee’s acceptance is assumed by the act of recording, etc.), though there are some exceptions or additional forms in certain jurisdictions (like a certificate of value, etc.). The key point: if you’re the grantor, make sure you sign the deed in front of a notary. If there are multiple grantors (e.g., co-owners), each grantor should sign. Use the name exactly as it’s typed under the signature line. If the deed says “John Q. Public, as Grantor” then sign “John Q. Public,” not “Johnny Public.” Consistency counts.

Now, notarization: In the U.S., virtually all deeds must be notarized to be recorded (and recording is essential – see Mistake 8). A notary public’s acknowledgment is the official way to verify that the signature on the deed is genuine and given voluntarily. If you fail to have the deed notarized, the county recorder will likely refuse to accept it. Even if you manage to hand the paper to the grantee, an un-notarized deed is highly problematic. It may not provide constructive notice to third parties, and it’s an easy target for challenges (someone could claim the signature is forged, etc.). In short: never skip the notary. It’s a simple step: just sign the deed in front of a licensed notary, and have them affix their seal and acknowledgment wording.

Additionally, some states require one or two witnesses to also sign the deed (in addition to notarization). For example, Florida requires two witnesses for deeds; Georgia requires one witness (plus the notary can act as a witness); other states, like California, don’t require any witness beyond the notary. Check your state’s requirements or consult an attorney if unsure. Failing to have the required witnesses can invalidate the deed or prevent recording. This is an easy mistake to avoid: if your state needs witnesses, bring a couple of friends or ask the notary if they can arrange witnesses. Many notaries will accommodate that. The witnesses will sign on the witness signature lines. Their job is to attest they saw the grantor sign the deed. If witnesses are required and you don’t have them, the deed might be considered defective.

Besides signatures and notarization, ensure you fill out any other execution details on the deed form. For instance, many deed forms have a line for the date of execution near the signature area – don’t leave the date blank. The notary will usually fill in the date in their acknowledgment too, but it’s good to have it in the body if indicated.

How to avoid this mistake

Always sign in the presence of a notary public. Do not pre-sign and then find a notary later. The notary needs to witness you signing. All grantors listed should do the same. Make sure you have proper ID when you go to notarize, as the notary will need to verify your identity.

After signing, the notary will complete the acknowledgment block. Ensure the notary uses the correct venue (state and county) and signs and stamps the document. An incomplete notary acknowledgment (missing seal or commission info) can also cause a recorder to reject the deed. Double-check that the notary’s seal is affixed and clear.

In summary, proper execution involves signed by grantor, witnessed if required, then notarized. It’s a simple formula, but absolutely essential. If you skip or botch these formalities, the quitclaim deed won’t do its job. As a final tip: don’t alter or white-out anything on a deed after it’s notarized; if you need to correct something, it’s better to re-do the deed rather than risk the appearance of tampering. Get it signed and notarized right the first time and you’ll save yourself a lot of trouble.

Mistake 8: Failing to Record the Deed with the County

After you’ve signed and notarized the quitclaim deed, you’re not quite done. One of the most crucial follow-up steps is to record the deed at the appropriate government office (usually the County Recorder or Clerk’s office where the property is located). Failing to record a quitclaim deed is a common mistake that can lead to big headaches down the road.

Recording a deed means filing the document in the public land records. This serves as official notice to the world that a transfer has occurred. If you don’t record the deed, several problems can arise:

Ownership ambiguity

If the deed isn’t recorded, from the public’s perspective the grantor still appears to own the property. For example, say Mary quitclaims a house to her brother John, but John never records the deed. Years later, Mary (or Mary’s heirs) could mistakenly or fraudulently sell the house to someone else, since the records show Mary as the owner. John’s unrecorded deed would likely lose out in a priority battle because the other buyer recorded their deed. An unrecorded deed “can present a problem” because it doesn’t inform third parties of the change in ownership. In some jurisdictions, an unrecorded deed might be considered void against later purchasers or creditors who didn’t know about it. In other words, not recording means your claim to the property isn’t protected against claims by others.

Difficulty proving ownership

If you’re the grantee and you hold an unrecorded quitclaim deed in your file cabinet, you might run into issues when you try to insure, mortgage, or sell the property. For instance, a title company asked to insure your ownership will check the county records. If they don’t see your name listed as owner (because you never recorded the deed), they will at minimum require the deed to be recorded, and they’ll scrutinize the gap in time. If the grantor has passed away or there’s some dispute by that time, you’re in for a legal mess.

Recording is what gives constructive notice to everyone else. Failing to record means you haven’t officially updated the public record of ownership and it means the ownership transfer is not officially recognized by the government.

How to avoid this mistake

Record the deed as soon as possible after it’s signed. The process is usually straightforward: you (or the grantee) take the original signed and notarized quitclaim deed to the County Recorder and pay a small recording fee. The recorder will stamp it, assign it a book and page or instrument number, and make it part of the permanent records. Many counties even offer e-recording through title companies or online services. When you record, you might also need to file a transfer tax form or exemption form, depending on your state and whether any tax is due for the transfer. The clerk can guide you on this. For example, many intra-family quitclaim deeds are exempt from transfer taxes but still require an exemption form to be filed.

Make sure the deed meets all requirements for recording. Original signatures, notary acknowledgment, proper formatting some places require certain margins or a preparer’s statement on the document. So do not be alarmed if you see extra space on the top margin of the first page. That space is reserved for the recorder to stamp the deed when it gets recorded. If in doubt, call the recorder’s office and ask what they require for a quitclaim deed. They might even have a checklist.

After recording, the office usually returns the original (or a copy) with a stamp. Keep that recorded deed in a safe place as proof of your ownership. The stamp or recording label on it is key. If down the line someone questions your title, you can point to the recorded deed and the public record.

In summary, don’t tuck the deed away in a drawer and forget it. Until it’s recorded, your job isn’t done. Many a quitclaim deed mistake story starts with “I never recorded it, and then… [insert problem].” So, deliver it to the county for recording immediately so it’s officially on the books.

Mistake 9: Using the Wrong Forms or DIY-ing Without Enough Knowledge

Last but certainly not least, a common mistake is attempting a “do-it-yourself” quitclaim deed with a subpar form or no guidance, leading to errors. In the age of the internet, many people Google terms like “free quit claim deed form”, “quitclaim deed form free download”, or “online quit claim deed template”. While it’s great that these resources exist, not all forms are created equal. Using a random template without understanding it can result in a deed that is invalid or doesn’t do what you think it does.

- Outdated or Generic Forms: Real estate laws and formatting conventions can vary by state. A generic quitclaim deed form you found online might not comply with your state’s requirements. For instance, some states require specific language, margins, or addendums (like a legal description attachment, a drafter’s identity, etc.). If you use a one-size-fits-all form, you might inadvertently omit something important. Blank spaces can be another issue. Some people download a form and don’t fill it out completely or correctly. Any blank line on a deed, like failing to insert the grantee’s name, or not specifying the county, can be problematic. We’ve seen deeds where folks didn’t realize they had to add a notary acknowledgment page, so they turned it in without notarization

- Insufficient Guidance: Without experience, you might not catch mistakes. For example, you might not know you need to include a preparer’s name at the bottom (“This document prepared by…”) in some states, or that you should add a mailing address for tax notices. Little details can vary. Doing it entirely on your own using a one-size-fits-all online form means you might miss those nuances.

- Typos and Handwriting Errors: Many DIY deeds are handwritten or have corrected typos. While a typo doesn’t automatically invalidate a deed, certain ones can, like a misspelled name or wrong legal description as discussed.

How to avoid this mistake

Use online forms (such as Ziji Legal Forms) that are created by lawyers, constantly updated as per legal regulations, and take into consideration the different nuances that come with creating quitclaim deeds in different states. Our platform asks you the necessary questions (names, addresses, property info etc) and then generates a deed document that’s properly formatted for your state. The advantage is that they are designed to avoid the common mistakes. For example, we won’t let you leave out the legal description or the grantee’s name, and we also include the correct notary acknowledgment wording automatically. This removes a lot of the guesswork.

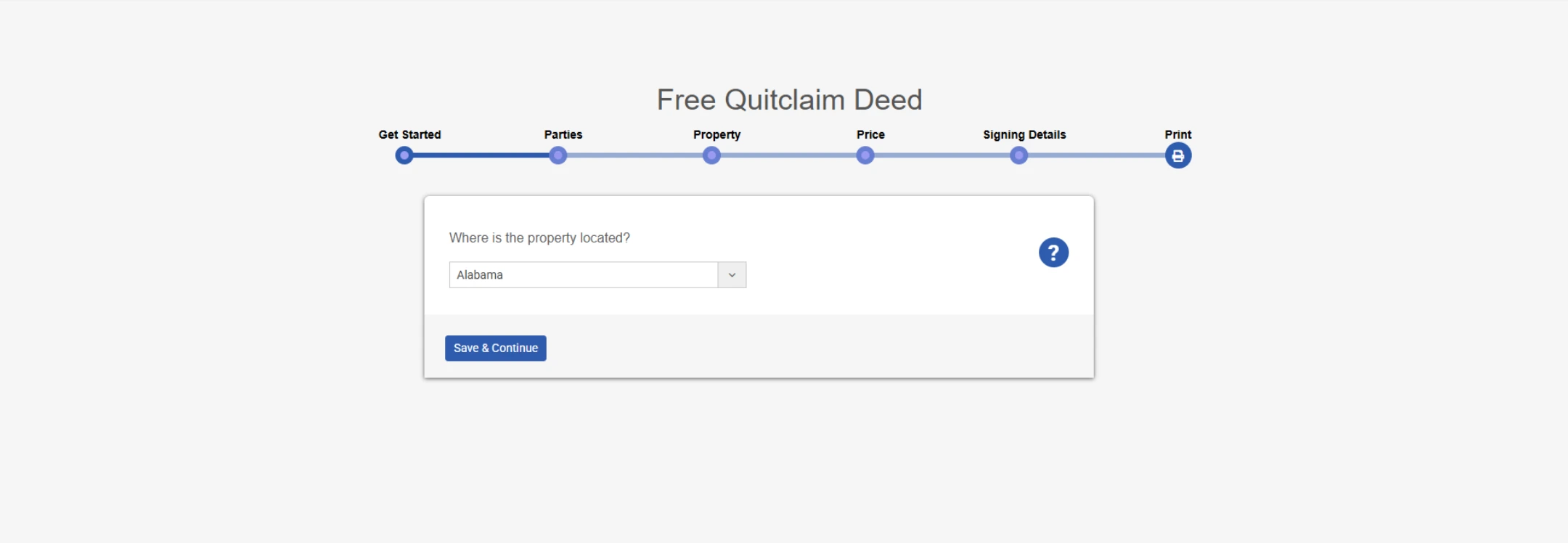

How to Create a Quitclaim Deed Correctly with Ziji Legal Forms (Step-by-Step)

To illustrate a hassle-free way of avoiding many of the mistakes discussed, let’s walk through how you can create a proper quitclaim deed using Ziji Legal Forms. Ziji Legal Forms is an online platform that helps you generate legal documents by guiding you through a series of questions. By using such a guided service, you ensure that all the necessary information is included and correctly formatted. Here’s an overview of the process, with placeholder screenshots for each step:

1. Start and Select the Quitclaim Deed Template

Log in to Ziji Legal Forms and navigate to the real estate or property forms section. From the dashboard, select the Quitclaim Deed form.

2. Enter the Grantor and Grantee Details

The system will prompt you to fill in the parties’ information. You’ll enter the grantor’s name and address and the grantee’s name and address in the appropriate fields. Ziji’s interface will ensure you don’t forget details like middle initials or suffixes if they’re part of the legal name.

3. Input the Property Information

Next, you’ll input the property details. This includes the property’s legal description of the property. Ziji provides guidance on where to find the legal description (for example, from your previous deed or tax statement). You’ll type in or paste the full legal description.

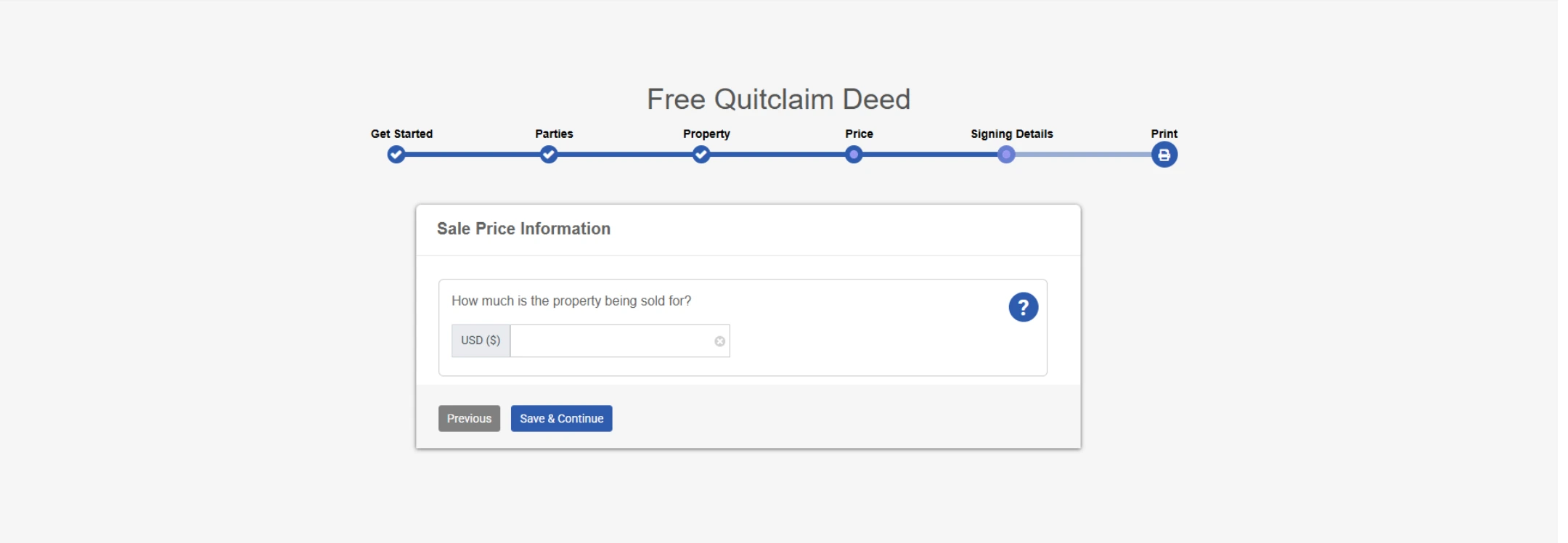

4. Specify Consideration and Other Clauses

The form will ask if any payment (consideration) is given for the transfer. For family gifts, you might enter “$0 – gift” or a nominal amount like $10. If your state requires a specific phrasing (e.g., “Ten dollars and other good and valuable consideration”), the platform may auto-fill that once you indicate it’s a gift transfer. Additionally, if your state has any unique requirements like a preparer’s name, or a return address after filing, Ziji Legal Forms will include those in the workflow.

5. Review Auto-Generated Deed Preview

After filling in the questionnaire, Ziji will generate a preview of your quitclaim deed with all the information plugged into the correct legal format. You can review the document on screen to double-check all names, descriptions, and details are correct. This preview lets you verify that, for example, spelling is correct and the legal description matches the source. If you see anything off, you can go back a step and edit the input.

6. Finalize and Download the Quitclaim Deed

Once everything looks good, you’ll finalize the document. Ziji will then allow you to download the quitclaim deed as a PDF or Word document. The downloaded deed will be professionally formatted, usually including lines for the grantor’s signature, notary acknowledgment, and any witness lines if needed for your state. All the required elements like the venue, preparer info, and mailing address for recording, will be present, based on the info you provided.

After downloading, you’ll print the deed. Then you follow the standard procedure of signing it in front of a notary, and witnesses if required.

By using Ziji Legal Forms in this way, you effectively sidestep many of the pitfalls we’ve outlined: the form won’t let you forget key information, it will use the right language for your jurisdiction, and it produces a clean document. The result is a quitclaim deed that is ready to sign, notarize, and record without fuss.

Why this helps

The guided experience means you don’t have to be a legal expert to get it right. It’s like having a virtual checklist built into the process. This reduces the risk of mistakes such as missing a name, messing up the legal description, or using wrong wording. In short, Ziji Legal Forms make the process of creating a quitclaim deed simple, fast, and legally sound, even for first-time users.

Conclusion

Quitclaim deeds are a handy legal tool for transferring property under the right circumstances, but as we’ve seen, there are many mistakes that can occur if you’re not careful. By understanding what a quitclaim deed does, and doesn’t do, you can avoid the misconceptions that trip people up. Always remember that a quitclaim deed comes with no guarantees of title. It’s the ultimate “buyer beware” deed. Therefore, use it in appropriate situations, typically with trusted parties or simple corrections, and not in high-risk deals.

With the right approach, a quitclaim deed can solve problems, such as quickly transferring ownership to a loved one or correcting a title error, rather than create new ones. If you ever feel unsure, remember that resources are available to guide you. Ziji Legal Forms can walk you through creating a solid quitclaim deed step-by-step with a competitive price, and local attorneys are just a call away for advice tailored to your situation.

In conclusion, a quitclaim deed is a powerful tool when used correctly. Avoid the nine mistakes we’ve outlined, and you’ll ensure that your property transfer is smooth, valid, and trouble-free. Here’s to making your quitclaim deed experience quick, and correct!

Quitclaim Deed FAQs

Can a quitclaim deed be reversed or canceled?

A quitclaim deed can only be reversed if both parties agree, typically by executing a new deed transferring the property back.

Does a quitclaim deed affect the mortgage on the property?

No, a quitclaim deed only transfers ownership, not financial responsibility. The original owner may still be liable for the mortgage.

Is a quitclaim deed valid without recording it?

It may be legally valid once signed and notarized, but not recording it can lead to future disputes or issues with title clarity.

Can I use a quitclaim deed to disinherit someone?

Not directly. A quitclaim deed is used to transfer property, not to remove future inheritance rights, estate planning tools are better suited for that.

What are the risks of accepting a quitclaim deed as a buyer?

The grantee receives no title protection or guarantees. There could be unknown liens, claims, or title defects.

What jurisdictions can use our quitclaim deed?

You can use our template to create a legal and valid quitclaim deed for the following jurisdictions:

| Alabama (AL) | Alaska (AK) | Arizona (AZ) | Arkansas (AR) | California (CA) |

| Colorado (CO) | Connecticut (CT) | Delaware (DE) | District of Columbia (DC) | Florida (FL) |

| Georgia (GA) | Hawaii (HI) | Idaho (ID) | Illinois (IL) | Indiana (IN) |

| Iowa (IA) | Kansas (KS) | Kentucky (KY) | Louisiana (LA) | Maine (ME) |

| Maryland (MD) | Massachusetts (MA) | Michigan (MI) | Minnesota (MN) | Mississippi (MS) |

| Missouri (MO) | Montana (MT) | Nebraska (NE) | Nevada (NV) | New Hampshire (NH) |

| New Jersey (NJ) | New Mexico (NM) | New York (NY) | North Carolina (NC) | North Dakota (ND) |

| Ohio (OH) | Oklahoma (OK) | Oregon (OR) | Pennsylvania (PA) | Rhode Island (RI) |

| South Carolina (SC) | South Dakota (SD) | Tennessee (TN) | Texas (TX) | Utah (UT) |

| Vermont (VT) | Virginia (VA) | Washington (WA) | West Virginia (WV) | Wisconsin (WI) |

| Wyoming (WY) |

GET STARTED FOR FREE

Create your

Get Started For Free